“I have a self to recover, a queen.”

The bee was half-dead on my windowsill, wings twitching like paper in wind. I found a teaspoon, filled it with sugar water, and left it by her body like an offering. The bee inched toward it slowly, then drank, legs splayed wide. It was obscene and holy, watching a creature return from the brink by sheer will and sweetness.

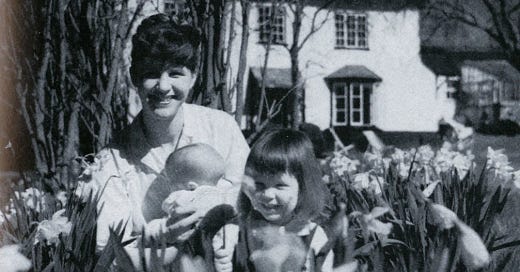

Near the end of her life, in Devon, Sylvia Plath took up beekeeping. Her father had been an expert in bees. Her husband was away. She was writing with a new urgency, feeding her children, facing a storm of psychic weather, and still: the bees. The hive. The sting and the sugar. She wrote a whole sequence in October 1962. Five poems that are neither cosy nor quaint. They’re vivid, erratic, and crackling with symbolism.

The first of the bee poems, “The Bee Meeting”, is an ambush. A dream-sequence in daylight. The speaker is stripped of identity, clothing, and agency. She’s led to a field by faceless people, villagers with ritual tools, and she doesn’t know why. The bees are barely in it yet. What’s really happening is a metaphoric initiation. Into womanhood, into writing, into being observed and objectified. Or maybe into revolt. She’s both afraid and hyper-aware: “I am nude as a chicken neck, does nobody love me?” It’s both childish and devastating. Critics have read this as Plath exploring the violence of submission, but it could also be read as the start of a spell. A stripping-down. The beginning of transformation.

Then comes “The Arrival of the Bee Box”—a small black cube teeming with threat:

“The box is locked, it is dangerous. / I have to live with it overnight / And I can’t keep away from it.”

The threat is sealed but intimate: unseeable, unknowable, and yet inescapably close. Plath renders psychological terror as confinement: a space without windows, without exit, where something swarms just out of sight. The speaker is both jailer and captive, drawn to the danger she cannot name. It’s a metaphor not just for madness but for the lure of what language can’t quite hold.

She bought it. It’s hers. But she doesn’t know what to do with it. The box could be her subconscious, her rage, her creativity, even her ancestry. It’s dangerous and teeming. She’s afraid of letting it out. Afraid of being consumed. Even her syntax hums with threat. The clauses are clotted, enjambments abrupt. The lines don’t flow; they crawl and twitch. Language becomes a swarm: teeming, dangerous, alive. Still, she’s the keeper. The final line, after all that chaos, is devastatingly soft: “The box is only temporary.” Is that a promise or a threat? Maybe both.

By the time we get to “Stings”, something has changed. The disorientation of the earlier poems gives way to a clearer, more defiant self. The speaker is no longer passively observed but actively participating: “Bare-handed, I hand the combs.” She works alongside a man, but her focus isn’t on him. It’s on the hive, the queen, and the unspoken hierarchy of women. The queen is found in a diminished state:

“Her wings torn shawls, her long body / Rubbed of its plush— / Poor and bare and unqueenly and even shameful.”

Yet, the speaker rejects the role of drudge: “I am no drudge / Though for years I have eaten dust.” What follows is one of the most electrifying moments in the sequence: “I have a self to recover, a queen.” This isn’t restoration—it’s resurrection. The queen rises, “red / Scar in the sky, red comet” a figure of fury and survival. Even after grief, after labour, after being nearly destroyed, she flies again. She’s not beautiful, but terrible. Not gentle, but alive.

“The Swarm” feels like a detour at first. It’s more historical than personal, but it pulses with the same wild energy. The hive becomes a war machine, crossing countries and splintering into violence. Bees aren’t symbols of order here; they’re erratic, dumbly obedient, used. Napoleon rides through the poem like a fever dream, a figure of ambition and collapse. “Pom! Pom!” goes the gunfire, or the typewriter, or maybe just the heart. Even now, the hive must be controlled, shot down from the tree, “so dumb it thinks bullets are thunder.” Even so, it persists. Plath turns the swarm into a vision of power: dispersed, disgraced, but not defeated. The man with “gray hands” watches, smiles, and survives. So does Napoleon. So do the bees.

Then, “Wintering”. This bee poem is quiet. It is winter. The speaker is storing honey. The queen sleeps. The men are gone. There’s an eerie peace in this poem. It’s not triumphant. The hive has changed. The speaker has changed, too. No more rituals of stripping or madness or metaphor made flesh. Just bees, and sugar, and survival: “They taste the spring.” But winter is never gone for good. The sugar is temporary. The sting endures.

I return to these poems because I read them not just with my eyes, but with my nerves. They are alive, dangerous, and defiant. They make no effort to be polite. They are about creation, power, entrapment, rebirth. About the body, about womanhood, and history. They speak, too, to that fragile, twitching moment when something might still be saved, even if only with a spoonful of sugar.

Thank you for this. It's a pleasure to read your academic pieces as you write with a clarity like sunlight through leaves. I enjoy these immensely; this one in particular because I have four hives and know nothing of Plath's encounters with them.

fantastic... i would read an entire book of your essays on plath